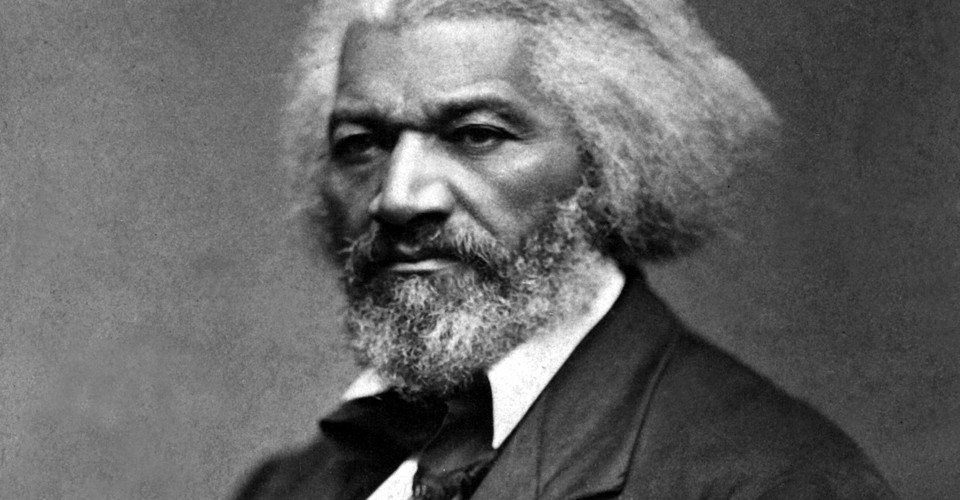

Frederick Douglass played a massive role during the abolitionist movement. He advocated for the emancipation of slavery. He devoted his life fighting for equal rights. During the Civil War, Douglass met President Abraham Lincoln only a few times. “Yet, they developed parallel and complementary goals and strategies to end slavery.”[1] Douglass was a candid critic of Lincoln’s until the Emancipation Proclamation. To this point of his life, he fought for freedom for all African Americans. But, how did Frederick Douglass perceive President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation? Did his views change over time or remain the same?

Frederick Douglass was born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey in Tuckahoe, Maryland. His story is remarkable and known to many American students. “The life of Frederick Douglass is the history of American slavery epitomized in a single human experience.”[2] His family was owned by Captain Aaron Anthony. Captain Anthony had several plantations with over thirty slaves.

Douglass did not have a close relationship with his mother and called his father “a white man”.[3] Although, he did not know if this was accurate. Around the age of 7 or 8, he was sent to Baltimore by his master, Colonel Lloyd. It was in Baltimore; Douglass learns how to read and write by Mrs. “Sophia” Auld. He learned his first impression of slavery during this time. At a young age, the “thought of being a slave for life began to bear heavily upon my heart”.[4] As Douglass grew older, he educated himself and learned about the abolitionist movement. “Very often I would overhear Master Hugh, or some of his company, speak with much warmth of the abolitionist”.[5]

Douglass was sold several times, jumping from farm to farm. He became depressed and felt it would never end. However, it was an incident with one of his masters that changed his path. In his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, he explains in detail the battle he had with Mr. Covey. “The battle with Mr. Covey was the turning point in my career as a slave.”[6] Four years later, Douglass escaped from slavery, “reaching New York without the slightest interruption of any kind”.[7]

While in New York, Douglass decided to change his name when concerns grew that he could be captured. It was four months after the escape, Douglass read issues of The Liberator. The readings gave him motivation; “my brethren in bonds-its scathing denunciations of slaveholders-its faithful exposures of slavery- and its powerful attacks upon the upholders of the institution”.[8] He joined the anti-slavery movement and decided to tell his story of bondage to freedom.

Douglass moral basis was to advocate for black patriotism and encourage groundbreaking change. However, by 1862, like many abolitionists, Douglass believed in the evils of the South rather than “Northern virtue”.[9] He believed there were two loyalists and they spoke alike in the Union. Both wanted to end the war, but one group wanted to end slavery and the other was against abolishing slavery. It wasn’t until March 6, 1862, Douglass began to alter his views. Lincoln requested Congress to authorize funds for gradually compensating emancipation “for the border slave states still in the Union”.[10] This provided progressive change to the Union and it sent a message to the Confederate States.

Historian David Blight, an expert in African American studies explains in his book, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, Douglass began to breath a new tone, “it is really wonderful”.[11] Douglass added “how all efforts to evade, postpone, and prevent its emancipation coming have been mocked and defied by the stupendous sweep of events”.[12] This recommendation by the President delighted Douglass. He started to believe the nation was growing and Lincoln’s views were imperative to the nation’s health, “he is tall and strong, but is not done growing; he grows as the nation grows”.[13] Blight articulated that Douglass warmed up to the President at this moment.

President Lincoln felt he needed to take another drastic step. On a trip with the Secretary of Navy, Gideon Welles and Secretary of State Steward, he stated, “unless the Rebels ceased the war-and he saw no evidence they would – he would take a drastic step”.[14] Strategically, he felt the Union had to free the slaves, so on July 22, 1862, he read the first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation. The Proclamation was not declared until January 1, 1863. The Proclamation did not actually free any slaves as there was no way to enforce it in states that were still under the Confederates control. But, the Proclamation “represented a symbolic landmark for the nation that purported to live by the words of the Declaration of Independence”.[15]

It shouldn’t be a surprise; Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was met with resistance. In an article on October 5, 1862 by the New York Herald, it provides details of the reaction by citizens of Richmond. There were resistance and suggestions that anyone against the Confederate should be put to death. Samuel Clark of the Missouri Artillery Unit believed Jefferson Davis “should be authorized immediately to proclaim that every person found in arms against the Confederate government and its institutions on our soil should be put to death”.[16] The South reaction was anticipated, but it was abolitionists especially Douglass that amazed Lincoln.

When Lincoln issued the preliminary draft in July 1862, some wondered if it was too late. Frederick Douglass was one of those critics. He admitted “disappointment that the Proclamation was so modest in its demands and so legalistic in tone”.[17] Douglass felt the wordings lacked moral regret towards slavery. He felt that the Proclamation needed to completely disenfranchise the institution of slavery. The nation should’ve felt disgraceful not to end slavery sooner. Although, this was simply the first draft, it was not met as kindly as Lincoln expected from abolitionist and Douglass.

Douglass’s tone did alter after the proclamation was signed. But, it was not long, as Douglass understood the proclamation was supposed to end slavery “but never destroyed” it.[18] He pointed out several examples why he believed this statement, “when the government persistently refused to employ colored troops-when the emancipation proclamation of General John Fremont, in Missouri, was withdrawn-when slaves were being returned from our lines to their masters” are just a few examples.[19] He quoted Secretary of War, William Seward had given notice to the nation that “the war for the Union might terminate, no change would be made in the relation of master and slave”.[20]

Like David Blight, historian Graham Culbertson explains in an article, Douglass believed the primary goal was to preserve the union and not end slavery. However, it was the Proclamation that brought a sense of belief that change was coming. Douglass echoed Pierre L’Enfant’s idea on how to bring the nation to the middle, “kill slavery at the heart of the nation, and it will certainly die at the extremities”.[21] Douglass believed as long as there was Southern culture in Washington, slavery would never be completely abolished.

Lincoln did not officially declare the final draft until January 1, 1863 almost 5 months after the initial draft. Douglass explains in his autobiography many years after the proclamation was signed, “this Proclamation changed everything. It gave a new direction to the councils of the Cabinet, and to the conduct of the national arms.”[22] During his speech of the Boston celebration on January 1, he had “more emotional veracity” than any other.[23] This tone was different than a few months earlier. There was relief that Lincoln did not lessen the magnitude to this important declaration.

James McPherson, a Civil War historian, writes many abolitionists and radical Republicans mirrored Douglass words, “to fight against slaveholders, without fighting against slavery, is but a half-hearted business”.[24] McPherson explained the Proclamation changed the war for the North. It moved “from one to restore the Union into one to destroy the old Union and build a new purged of human bondage”.[25] Douglass was invited to the White House by Lincoln. During his meeting with Lincoln, Douglass grasped a better picture of Lincoln intentions. He had both positive and negative reviews about the Proclamation. But the meeting showed Lincoln had “a deeper moral conviction against slavery than I have ever seen before in anything spoken or written by him”.[26]

Graham Culbertson explains during the unveiling of Freedmen’s Memorial Douglass seemed farsighted. Douglass had positive and negative reviews about the Proclamation since its first draft. In 1876, it was no different, Lincoln “was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights of humanity in the colored, people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country”.[27] However, Douglass did celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation for many years after the war. On the first week of January, many abolitionists and freed slaves celebrated the anniversary of the Proclamation. Douglass stressed the event that occurred under Lincoln’s Presidency. He explained if anyone tries to downplay the event, African Americans “should calmly point to the monument we have this day erected to the memory of Abraham Lincoln”.[28] Douglass appreciated Lincoln at times and the Proclamation, but his rhetoric changed from time to time.

African Americans were struggling to find its path during the Reconstruction era. Douglass took note and continued to speak about the treatment of his people. It was doing an Emancipation Proclamation anniversary in New York; Douglass spoke about the importance of voting against politicians still bitter about the emancipation. “Each color voter of this State should say, in scripture phrase, may my hand forget its cunning and my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth if ever I raise my voice or give my vote for the nominees of the Democratic Party.”[29] Douglass constantly spoke about the importance to keep moving forward after emancipation occurred.

David Blight explains that Douglass felt responsible to remind the country about the genuine connotation of the Civil War and Proclamation. “Well the nation may forget; it may shut its eyes to the past, but the colored people of this country are bound to keep fresh a memory of the past till justice shall be done them in the present”[30] Douglass felt all Americans should never forget about the first day of January, 1863. He explains “can any colored man, or any white man friendly to the freedom of all men, ever forget the night” the proclamation was signed.[31] It was important for whites to appreciate black liberty and blacks to appreciate white “statesmanship”.[32]

Douglass perceived the Emancipation Proclamation as a step to a long quest for equal rights as written in the Constitution. The Proclamation was the first and most important step. Douglass spoke both favorably and with disappointment about the proclamation during his life. At times, he appreciated the Proclamation and it showed every year he gathered with other freemen to celebrate its anniversary. Douglass made it a point to remind both whites and black the importance of the document. Were there occasions Douglass felt the proclamation did not accomplish its task? Absolutely, these times were difficult for African Americans. Many felt they weren’t treated equally even after the Civil War. Research shows Douglass’s views on the proclamation alters throughout his lifetime.

Bibliography:

Blight, David W. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

Blight, David W. “”For Something beyond the Battlefield”: Frederick Douglass and the Struggle for the Memory of the Civil War.” The Journal of American History 75, no. 4 (1989): 1156-178.

Culbertson, Graham. “Frederick Douglass’s “our National Capital”: Updating L’Enfant for an Era of Integration.” Journal of American Studies 48, no. 4 (11, 2014): 911-35.

Douglass, Frederick, and Ruffin, George L. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. North Scituate: Digital Scanning, Incorporated, 2000. Accessed July 5, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Simon & Brown, 2012.

Douglass, Frederick, John W. Blassingame, John R. McKivigan, and Peter P. Hinks. The Frederick Douglass Papers. Series Two, Autobiographical Writings. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, n.d.

“Emancipation Celebrated: Frederick Douglass’s advice to the Colored People of New York at Elmira.” New York Times (1857-1922), Aug 04, 1880, 1.

“Frederick Douglass’s Rhetorical Legacy.” Rhetoric Review 37, no. 1, 2018, 1-76.

Guelzo, Allen. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2004.

Kelley, William Darrah, Wendell Phillips, Frederick Douglass, Elizur Wright, William Heighton, George Luther Stearns, and Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. The Equality of All Men Before the Law: Claimed and Defended. Boston: Press of Geo. C. Rand & Avery, 1865. Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926.

Masur, Kate. “The African American delegation to Abraham Lincoln: a reappraisal.” Civil War History 56, no. 2, (2010).

McFeely, William S. Frederick Douglass. New York: W&W Norton Company, 1991.

McPherson, James M. “How President Lincoln Decided to Issue the Emancipation Proclamation.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 37 (2002): 108-09.

Schaub, Diana J. “Learning to Love Lincoln: Frederick Douglass’s Journey from Grievance to Gratitude.” In Lincoln and Liberty: Wisdom for the Ages, edited by MOREL LUCAS E., by Thomas Clarence, 79-102. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2014.

Schneider, Thomas E. Lincoln’s Defense of Politics: The Public Man and His Opponents in the Crisis Over Slavery. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2006.

Shenk, Joshua W. Lincoln’s Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness. Houghton Mifflin Company: 2005

Sturdevant, Katherine Scott and Stephen Collins. “Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln on Black Equity in the Civil War: A Historical-Rhetorical Perspective.” Black History Bulletin 73, no. 2 (Summer, 2010): 8-15.

“President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation at Richmond–A Significant Sensation.” The New York Herald (1840-1865), Oct 05, 1862. 4.

Washington, Booker. Frederick Douglass. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Wickenden, Dorothy. “Lincoln and Douglass: Dismantling the Peculiar Institution.” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-) 14, no. 4 (1990), 102-12.

Wilson, Kirt H. “Debating the Great Emancipator: Abraham Lincoln and Our Public Memory.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 13, no. 3 (2010): 455-79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41936461.

[1] Katherine Scott Sturdevant and Stephen Collins. “Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln on Black Equity in the Civil War: A Historical-Rhetorical Perspective.” (Black History Bulletin 73, no. 2 Summer, 2010), 8

[2] Booker Washington, Frederick Douglass, (New York: Routledge, 2012), 1

[3] Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, (Simon & Brown, 2012), 4

[4] Ibid., 33

[5] Frederick Douglass and Ruffin, George L. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, (North Scituate: Digital Scanning, Incorporated, 2000), 108

[6] Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, 57

[7] Ibid., 83

[8] Ibid., 89

[9] David W Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 361

[10] Ibid., 363

[11] Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, 361

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., 364

[14] Ibid., 185

[15] Ibid., 261

[16] “President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation at Richmond–A Significant Sensation”, (The New York Herald, 1840-1865, Oct 05, 1862), 4

[17] Allen Guelzo, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America, (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2004), 180

[18] Douglass and Ruffin, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, 410

[19] Douglass and Ruffin, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, 410

[20] Ibid., 426

[21] Graham Culbertson, “Frederick Douglass’s “our National Capital”: Updating L’Enfant for an Era of Integration”, (Journal of American Studies 48, no. 4, 11, 2014), 929

[22] Ibid., 427

[23] William S. McFeely, Frederick Douglass, (New York: W&W Norton Company, 1991), 236

[24] James M. McPherson, “How President Lincoln Decided to Issue the Emancipation Proclamation”, (The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 37, 2002), 108

[25] Ibid., 109

[26] Dorothy Wickenden, “Lincoln and Douglass: Dismantling the Peculiar Institution.” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-) 14, no. 4 (1990), 102-12.

[27] Culbertson, Journal of American Studies 48, 935

[28] David W. Blight, “For Something beyond the Battlefield”: Frederick Douglass and the Struggle for the Memory of the Civil War”, The Journal of American History 75, no. 4, 1989, 1165

[29] “Emancipation Celebrated: Frederick Douglass’s advice to the Colored People of New York at Elmira”, (New York Times 1857-1922, Aug 04, 1880), 1.

[30] Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, 681

[31] Diana J Schaub, “Learning to Love Lincoln: Frederick Douglass’s Journey from Grievance to Gratitude.” In Lincoln and Liberty: Wisdom for the Ages, edited by Morel Lucas E., by Thomas Clarence, (Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2014), 92

[32] Ibid.